By the time Anastasius died, his successors Justin I (r. 518-527) and Justinian I (r. 527-565), devout Balkan westerners that they were and deep enthusiasts (particularly Justinian) for the Chalcedonian position, were too far behind to win the day for their creed. Justinian’s frustrated zeal will mark much of our story.

The end of Theoderic

Theoderic ended badly, and this was partly his fault. Think of him again as Othello—for his end shows his virtues as well as his defects, and the corrosive effect expectations can have on the best of intentions. Starting about 519, we have seen him reach back into his past, a past that was only myth, to bring forth stories of family and dynasty. In those stories, seventeen generations of his family, the Amals, through history, chronicle, and panegyric proclaimed Theoderic king of the Goths, on a Roman throne. Now the Gothic story began to be heard more clearly. No good came of it.

Meanwhile, Theoderic greeted the accession of Justin in Constantinople with a mixture of optimism and complacency. With hindsight, we can see that Justin’s regime was more of a threat than an opportunity for Theoderic, but Theoderic could not have known that. As the situation frayed around the edges of his regime, he may have been slow to see the coming dangers ski resorts bulgaria.

For one thing, churches were beginning to matter in the west in ways they hadn’t mattered before. With Rome and Constantinople (not to mention Clovis’s church to the northwest) all now in peace and harmony, Theoderic’s religious position began to make him seem strange and vulnerable.

And one most promising force was in eclipse. Vitalian, the best general in the east, could have been a friend for Theoderic and could have been a bridge between Ravenna and Constantinople, but things went badly for him and he left the scene a failure.

Vitalian was born in Zaldapa, just south of the Danube and not far from the Black Sea, in what is now northeastern Bulgaria or Dobrudja, to a family long at home there. His sons had names that sound barbarian, but his father was Patriciolus, and he had religiously enthusiastic relatives with the Greek names Stephanus and Leontius. Leontius was a distinguished theologian in the community of Scythian monks at Constantinople, a party that ferociously pursued compromise in matters of doctrine but could never quite succeed in propagating the compromises it reached. Vitalian may also have had an uncle who became Chalcedonian patriarch of Constantinople, only to be thrown out in 511 when the emperor Anastasius placated the monophysites.

Many scholars try to gothicize Vitalian and make him part of the families of Goths who chose not to go with Theoderic into Italy, but we need not accept the ethnic distinction to see the underlying fact. He was of an established family in the Balkans, the kind of family that produced generals and statesmen, and he was more like Theoderic than like the foot soldier Justin, who went to Constantinople to flee a life and likely death in the ranks of a general like Theoderic or Vitalian. Vitalian was short and he stammered, but he had spirit, and he became one of history’s great might-have-beens.

Under Anastasius

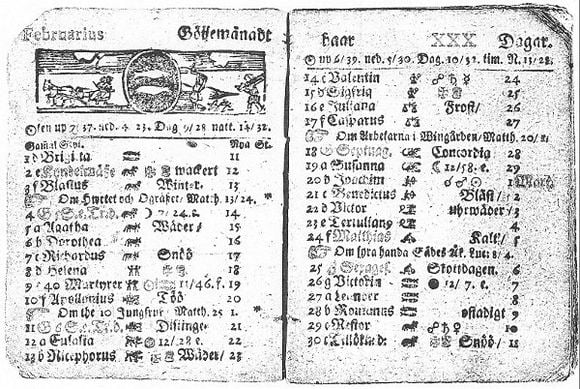

Under Anastasius in the 510s, Vitalian was the bulwark of empire on the Danube, but little respected by his monarch. He was an officer of moderate rank in 513 when—from Constantinople’s point of view—he led a revolt. He clamored for adequate supplies for his troops, known as foederati (allies)—sworn recruits either from across the river or from among peoples not yet habituated to Roman military service—but he quickly persuaded regular troops to join him. In short order, he found himself master of Thrace, lower Moesia, and Scythia—essentially all of modern Bulgaria and European Turkey Chronicle of Theoderic’s years in power.

He saw his moment and sought to take it, but in the end was never ruthless enough and never successful enough. He approached Constantinople with a large force spread out to fill the peninsula from the Sea of Marmara to the Black Sea, and rode unopposed to the city’s great Golden Gate. He presented himself as committed to supporting the Thracian army and the orthodox church (by which he meant the Chalcedonian one), and he made a credible case. After eight days of standoff, he allowed Anastasius to buy him off with reassurances.